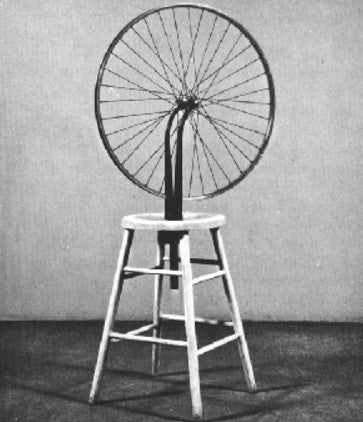

First coined by Dada artist Marcel Duchamp in the early 1900s, readymades have proven provocative, influential, and at times controversial, questioning the excesses of what was considered high art by placing commonplace objects on a pedestal of intellectual query and cultural regard, allowing the public to reconsider what is considered valuable and putting under scrutiny the uniqueness of the art object itself. Perhaps the earliest example of a readymade art object is the Bicycle Wheel created by Duchamp himself in 1913, where a bicycle wheel was placed atop a stool for a protest of sorts, challenging the importance given to objects of art and granting simple, everyday items an aura of mystique and elevated significance, confrontational and defiant. What is most fascinating is how the proliferation of readymades and the celebration of common objects influenced the perception and consumption of works that pervade our everyday, permitting us to see design with fresh eyes while evaluating these familiar, commonplace pieces with intellectual rigor and a searching of the soul, alluring, probing, and poetic.

This novel yet challenging notion of art as an intellectual exercise rather than a material process resulted in an emergence of the conceptual in art throughout the 20th century, beginning with “pure readymades” where a singular item was elevated to exulted consideration as with Duchamp’s Bottle Rack of 1914 and his now famous Fountain of 1917, a porcelain urinal that questioned the conception of the banal when intersected with impressions of high art, and expanding to the Pop Art movement of the 1950s and 1960s where commonplace objects taken from popular culture were featured as worthy of contemplation and respect and into the Conceptual Art movement where the artist’s idea was considered more noteworthy and significant than the final product itself. At the time, incorporating prefabricated, everyday objects in to works of art was understood as an assault on the conventional understanding of art, not only of its status, but also of its very nature. From historic pieces like Man Ray’s Gift of 1921 that features an iron with nails embedded on the plate, to Found Art pieces like to Mark Dion’s Cabinet from 2004 or Robert Rauschenberg’s First Landing Jump from 1961 and contemporary conceptual works from the likes of Damian Hirst, Felix Gonzalez Torres, and Tracy Emin, the influence of readymades and the use of mass-produced, common objects in art has marked a movement from the artist as maker to the artist as chooser, where the choice of the object itself is a creative act, and that art becomes thought provoking when such object is isolated from its use and granted a new meaning when presented in a gallery, deliberate, reflective, and precise.

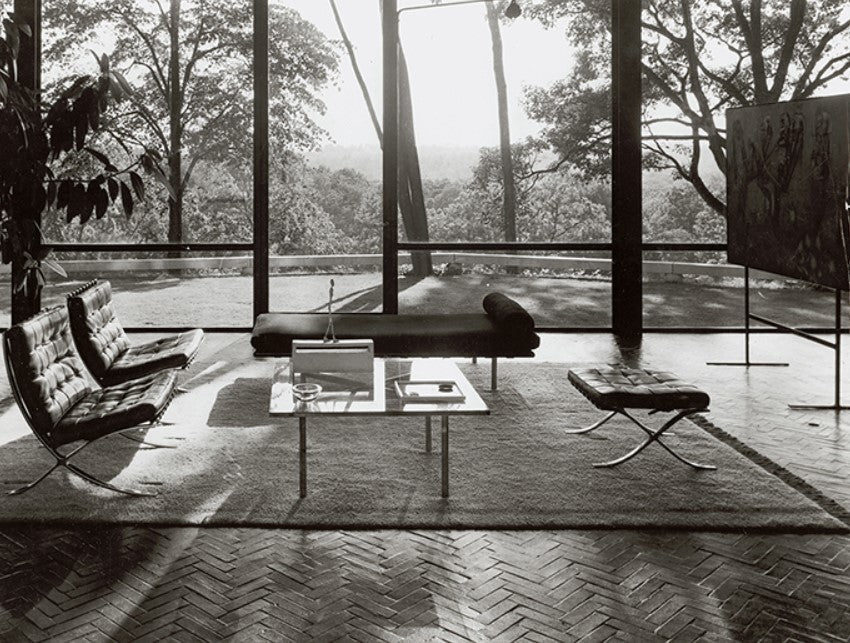

With the introduction of readymade art objects, the early 20th century notion of art as a transcendental exercise that representing only the highest cultural ideals was turned on its head, redefining what a celebrated art piece could be and at the same time elevating ordinary objects to works worthy of analysis and inquiry, addressing questions of usefulness and vigorous aesthetics. In this regard, the readymade movement granted a jubilation and exultation of common objects, allowing the public to consume everyday design with heightened awareness and well-considered attention to the artful exactitude and sublime use of the object, both emotional and practical. Whether resting on a Mezzadro stool from Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni, whose seat is taken from that of a tractor, or placing one’s drink on a Plane Coffee Table by Massimo Mariani for Living Divani, whose slab of wood or marble represents the expressive side of found objects and a delicate balance between solids and spaces, we craft living spaces that, while replete with objects considered common in their universal abundance and necessity to our daily routines, are also cleverly reimagined with an uncommon verve, understood as significant in their affect on our sociocultural landscape, and like readymades, elevating what could be considered banal to the enlightened and the artful, ushering a meaningful examination of what comprises our everyday, with grace, studied care, and awe-inspiring fortitude.

April 2024