From the asymmetrical, L-shaped Red House of 1859 that sparked the beginnings of the Arts and Crafts Movement and ushered a commitment to simple aesthetics largely devoid of ornament to the launch of the iPhone in 2007 with ground breaking technologies and a focus on the ease of user experience with streamlined aesthetics and intuitive design, modern history is peppered with moments that shaped our lived experiences and crafted the items we encounter every day, showcasing design as an ever-evolving living organism that transforms how we move through the world, influenced by the cultures that produce it while at the same time molding the societies that embrace it with new ways of perceiving ourselves and our relationship to the environments in which we live. From lectures and famous writings to exhibitions and the unveiling of life altering products, we look back on the moments of the last 150 years of design and highlight the most well-known and most impactful, whose culmination speaks to what makes good design great, with unparalleled usefulness, harmonious aesthetics, and an introspective reflection of how we live with one another in well-considered spaces.

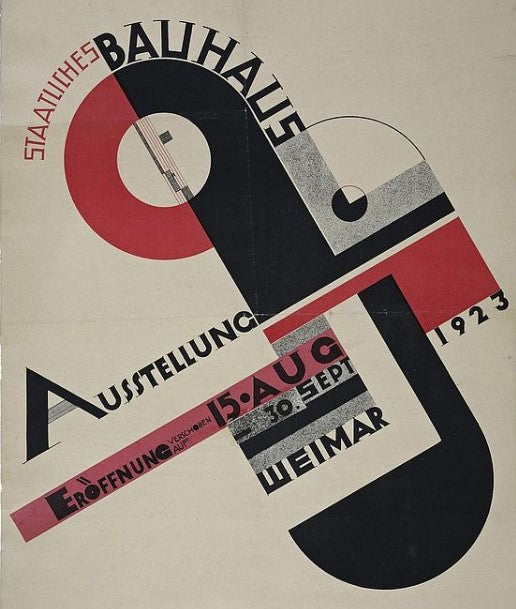

"Have nothing in your house you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful," William Morris once remarked, a central figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement whose faith in the ability of art to reshape society influenced design movements throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries. One moment which crowned the ethos of this movement while looking toward the future role of design in a well-balanced society was the forming of the Glasgow Four, whose unique style of work adapted some of the geometrical rigor of Frank Lloyd Wright and his Prairie School Houses with elements of the flowing forms that later became Art Noveau. Having met at the Glasgow School of Art in the mid-1890s, design legend Charles Rennie Mackintosh, James Herbert MacNair, and the sisters Margaret and Frances Macdonald with their creative alliance produced innovative and at time controversial designs that contributed to “Glasgow Style” and made way for a future where designs can be streamlined and well-balanced in geometry and proportion. In 1910, when Adolf Loos gave a lecture based on his 1908 essay Ornamentation and Crime, he suggested that the evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from utilitarian objects, a proposal that created a domino effect on future movements, including on that of De Stijl, whose 1918 manifesto defined good design as a move away from the individual toward universal laws of balance and harmony in art, illustrated by a use of simple geometries and vivid colors, that of Bauhaus, whose first exhibition in 1923 welcomed new technologies for many design classics, such as the Bauhaus lamp, making their mark on the world for their sophistication of simplicity, usefulness, and pioneering unity of art and design. It was then that Bauhaus founder, Walter Gropius gave his famous lecture on Art and Technology: A New Unity.

The years that followed ushered the birth of a modernist aesthetic, and in 1927 Charlotte Perriand cast aside the decorative, predominately wooden designs of the times for an aluminum, chrome, and glass room originally built on the top of floor of her apartment. This breakthrough piece called Le bar sous le toit (The bar beneath the roof) was seen by Le Corbusier and convinced him to welcome Perriand to his team, resulting in a series of cutting-edge furniture designs done with her influence that involved the tubular steel and clean forms of early modernism. As Le Corbusier looked at the home as a machine for living, the everyday objects that grace our homes earned esteem for their ability to govern our lives with ease and beauty, and by 1936 such items were welcomed in the Exhibition of Everyday Things, hosted by the Royal Institute of British Architects, elevating daily life to a milieu worthy of examination and celebration. These ideas began to take form in the United States not long after, when a wave of European modernists emigrated to the States to escape Nazi Germany. In 1938, Mies van der Rohe emigrates and becomes director of the Armour Institute in Chicago, later renamed the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he shaped a curriculum that influenced a generation of American architects and speckled the skylines of American cities with sleek, glass-skinned office and apartment towers. In 1940, the MoMA in New York held a competition on Organic Design in Home Furnishings, an aesthetic popularized by the Scandinavian designs of Arne Jacobsen and Hans Wegner, and this competition first introduced the world to the work of Eero Saarinen and Charles and Ray Eames. Organic design would remain of interest in the 1940s and the 1950s, when postwar technology made new materials like aluminum, steel, bonded wood, fiberglass, and plastics more readily available, enabling designers to experiment with new forms that remain popular today, as with the Eames’ molded fiberglass dining chairs and the Eames Lounge Chair for Herman Miller.

By the mid-50s and early 60s, the world began to look at product designs as equally worthy of respect and consideration for their role in helping people adapt to modernity and exist in the realm of dreams, desires, needs, and living habits. When Dieter Rams joined Braun in 1955, his philosophy of “less, but better” resulted in making Braun a household name with products like the SK 4 radiogram and the high quality D series, whose austere yet peaceful aesthetic allowed household appliances to blend seamlessly with their environment. This harmonious relationship between form and function followed into architecture, where Frank Lloyd Wright designed the Guggenheim Museum, which opened in 1959, as a testament to his belief that form and function should be one, joined in a spiritual union. Around the same time, Oscar Niemeyer was working with engineers, city planners, and other architects to design the new Brazilian capital of Brasilia. His government buildings, completed in 1960, explored the aesthetic of reinforced concrete and included buildings that seemed to float above the ground, supported by columns and allowing nature to flourish beneath. This was the first major city built entirely on the basis of the modernist principles of functionality and aesthetic. With the desire to make shelter more economically available to a large number of people, more comfortable and efficient, and applying modern technological know-how to architectural construction, Buckminster Fuller took modernism to a structurally interesting conclusion with his Geodesic Dome, unveiling the first large scale masterpiece in the US Pavilion at the 1967 Montreal World’s Fair, highlighting the impact of energy efficient design by decreasing surface area and thus allowing for fewer materials, creating a natural air flow and preventing radiant heat loss for optimal temperature regulation, uniting form and function in radical, fascinating ways.

Graphic design, too, saw many developments in good design as effective communication, making our experience with the world around us more pleasurable, efficient, and easily understood. One moment that stands out in modern design history is the unveiling of Massimo Vignelli’s New York Subway Map in 1972, whose value on logic over aesthetics helped people navigate a complicated system and remains today effective in clarity and pleasing to the eyes. That same year, the exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape opened at the MoMA and celebrated a sleek minimalism espoused by the likes of Mario Bellini and Achille Castiglioni, illustrating a counter-design approach where less is more and where the beauty of everyday objects can be found in their well-crafted simplicity. This marked a trend for embracing works later on in the decade like Glass Chair by Shiro Kuramata in 1976 and the Chair 77 by minimalist designer Bruno Ninaber van Eyben in 1977. Yet while on one hand, the purity of form and clean minimalism of these designers gained popularity in vein of modernist traditions, other designers chose to defy convention with brightly colored, oddly shaped, and generally outrageous objects like those in the Memphis Group, founded in 1981 by Ettore Sottsass. This gave way to a post-modernist embrace of works like the Wink chair by Toshiyuki Kita or the Green Street Chair by Gaetano Pesce.

As the 1980s indeed saw a rise of vivid color and uncommon forms, there was a movement to maintain a disciplined, monochromatic approach to interiors, as demonstrated with Andrée Putman’s interiors for the Morgans Hotel in 1984, ushering in the beginning of the boutique-hotel era. There was likewise a desire to elevate design that was emotive and intuitive, as Paul Rand expressed at his 1988 Symposium at the School of the Visual Arts, where he detailed that design is, in fact, everything, that to design is “much more than simply to assemble, to order, or even to edit: it is to add value and meaning, to illuminate, to simplify, to clarify, to modify, to dignify, to dramatize, to persuade, and perhaps even to amuse.” That same year Jasper Morrison curated a selection of simple yet beautiful everyday things in his first Super Normal Exhibition Some New Items for the Home, Part 1 in Berlin, a precursor to the famous 2006 exhibition coordinated with renown designer Naoto Fukasawa that highlights the design of objects that are made transcendent when reduced to their essentials, intuitive in use and resonant in emotionality.

By 1992, ergonomics and design for the digital age became more a focus of manufacturers like Humanscale and Steelcase, and it was at this time that Herman Miller’s Aeron chair was revealed, redefining task seating in workplace design. As the 20th century gave way to a 21st century, skylines across the globe were infused with the fluid forms of Zaha Hadid, whose remarkable contributions to architecture and design earned her the honor of the first woman ever to be granted the Pritzker Prize in 2004. For Hadid, architecture was meant to “excite you, to calm you, to make you think.” For others, architecture and design should likewise remain socially responsible and environmentally sustainable, an interest that has marked the current age with a green zeitgeist, as laid out in the publication of Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things from 2002 and in Norman Foster’s TED Talk of 2011, where he asserts that the environmental impact should be considered in designs made today, in a response to the specific climate and culture of a particular place. In all, these moments that brought us the best in modern and contemporary designs of the last century and a half have defined what it means to live with good design, enriching our lives with usefulness and beauty, and as Norman Foster noted, designing for the present, with an awareness of the past, and a future which is essentially unknown.

April 2024